On December 1st, Zillow quietly stripped climate risk scores from every listing on its platform. Gone. Over a million properties. The California Regional Multiple Listing Service had complained the data was "hurting sales." Real estate agents called the flood and fire warnings "big, scary labels."

Here's what Zillow didn't mention: the data worked. First Street's climate models—the same ones Zillow just buried—have consistently outperformed FEMA's official hazard maps at identifying properties in high-risk zones. The company's research shows properties in areas they flag as high-risk experience measurably higher flood damage and foreclosure rates than FEMA-designated zones would predict.

The data was accurate. And the industry buried it anyway.

Meanwhile, five days before Zillow's retreat, a Dutch startup called Overstory announced a $43 million Series B to help utilities identify which trees might knock out power lines. They serve six of the ten largest utilities in the Americas. PG&E's VP of Wildfire Mitigation called their satellite intelligence "transforming how utilities think about wildfire prevention."

Two moves. Same week. One company hiding data because it's too scary. Another raising $43 million because utilities are desperate for it.

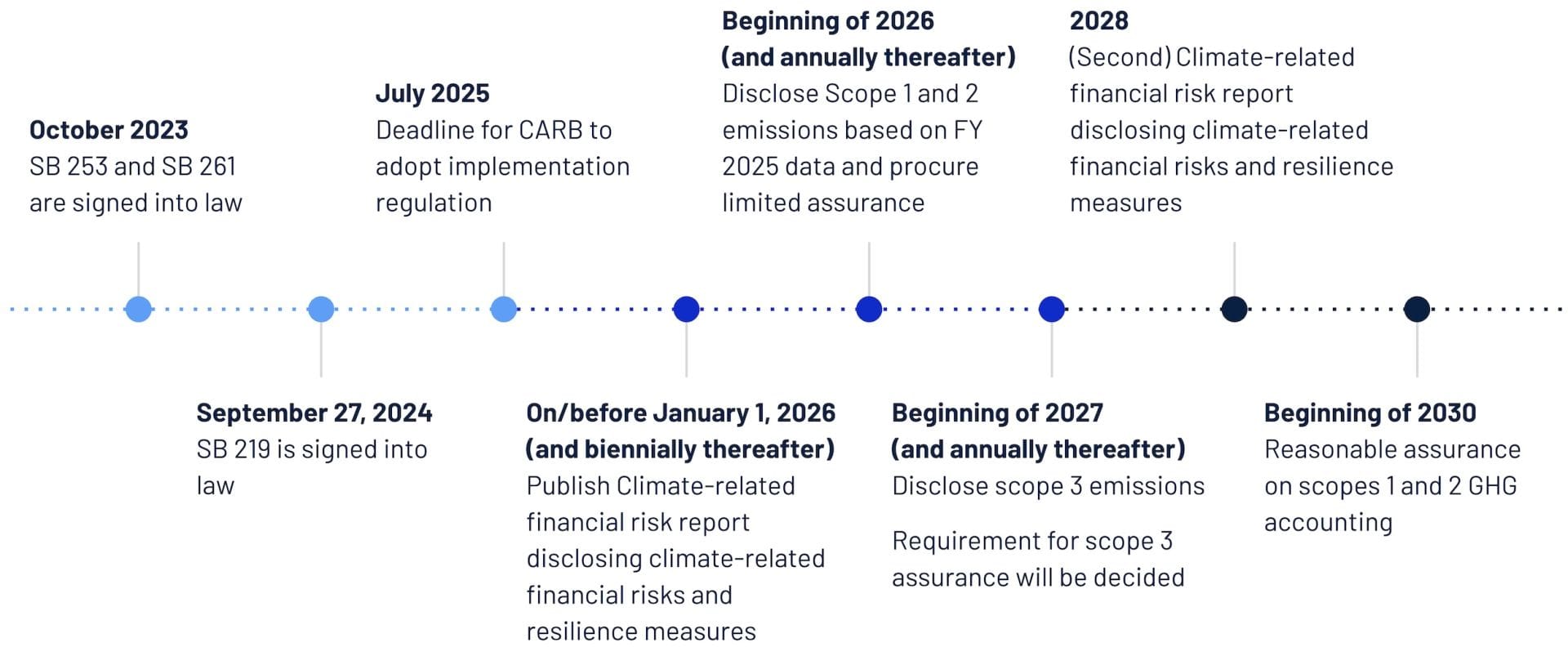

The signal is screaming: climate risk is no longer optional. It's just moving backstage—into the boardrooms, the regulatory filings, and the compliance documents where the real money changes hands.

The Zillow Lesson: Consumer-Facing Climate Data Is Radioactive

If you want to see how not to monetize climate data, study Zillow's face-plant.

Zillow rolled out climate risk scores in September 2024—fire, flood, heat, wind, air quality—using data from First Street. In surveys, more than 80% of buyers said they cared about climate risk. Obvious product. Clear demand.

Then reality hit.

Agents complained the scores were "inaccurate," "confusing," and worst of all... "killing deals." One agent in Massachusetts told the Boston Globe the risk scores were "putting thoughts in people's minds about my listing that normally wouldn't be there." A couple in Chappaqua, New York sued Zillow for $500,000, claiming the flood score "stigmatized" their home as "materially unsellable."

Under pressure from the California Regional MLS—the largest in the nation—Zillow ripped climate scores off the main listing view. Users now have to click out to First Street's site to see them.

Redfin went the opposite direction. They kept the exact same First Street data and doubled down. "Homebuyers want to know, because losing a home in a catastrophe is heartbreaking, and insuring against these risks is getting more and more expensive," Redfin's chief economist said.

Here's the lesson:

Putting scary climate numbers in front of consumers is politically explosive. But behind closed doors, climate numbers are quickly becoming non-optional. Utilities, insurers, and lenders don't get to say, "Let's hide that flood risk; it hurts the vibe." Regulators, rating agencies, and reinsurers are literally writing climate into the rules of survival.

The "Zillow climate widget for homebuyers" is a fragile wedge.

The real money is in the boring, back-office, must-do workflows where climate risk is now welded into law.

The Billion-Dollar Week That Rewrote the Rules

California's FAIR Plan—the insurer of last resort—hit 555,868 policies in March 2025. That's up 104,000 policies in just six months. The plan now has over $458 billion in statewide exposure, tripled from recent years as private insurers fled the market.

In January, the L.A. fires burned through Pacific Palisades and Altadena. The FAIR Plan reported roughly $4 billion in estimated losses. Commissioner Ricardo Lara approved a $1 billion assessment on insurance companies—the first in over 30 years. Half of that gets passed directly to homeowners.

The FAIR Plan is now seeking a 36% rate increase just to stay solvent.

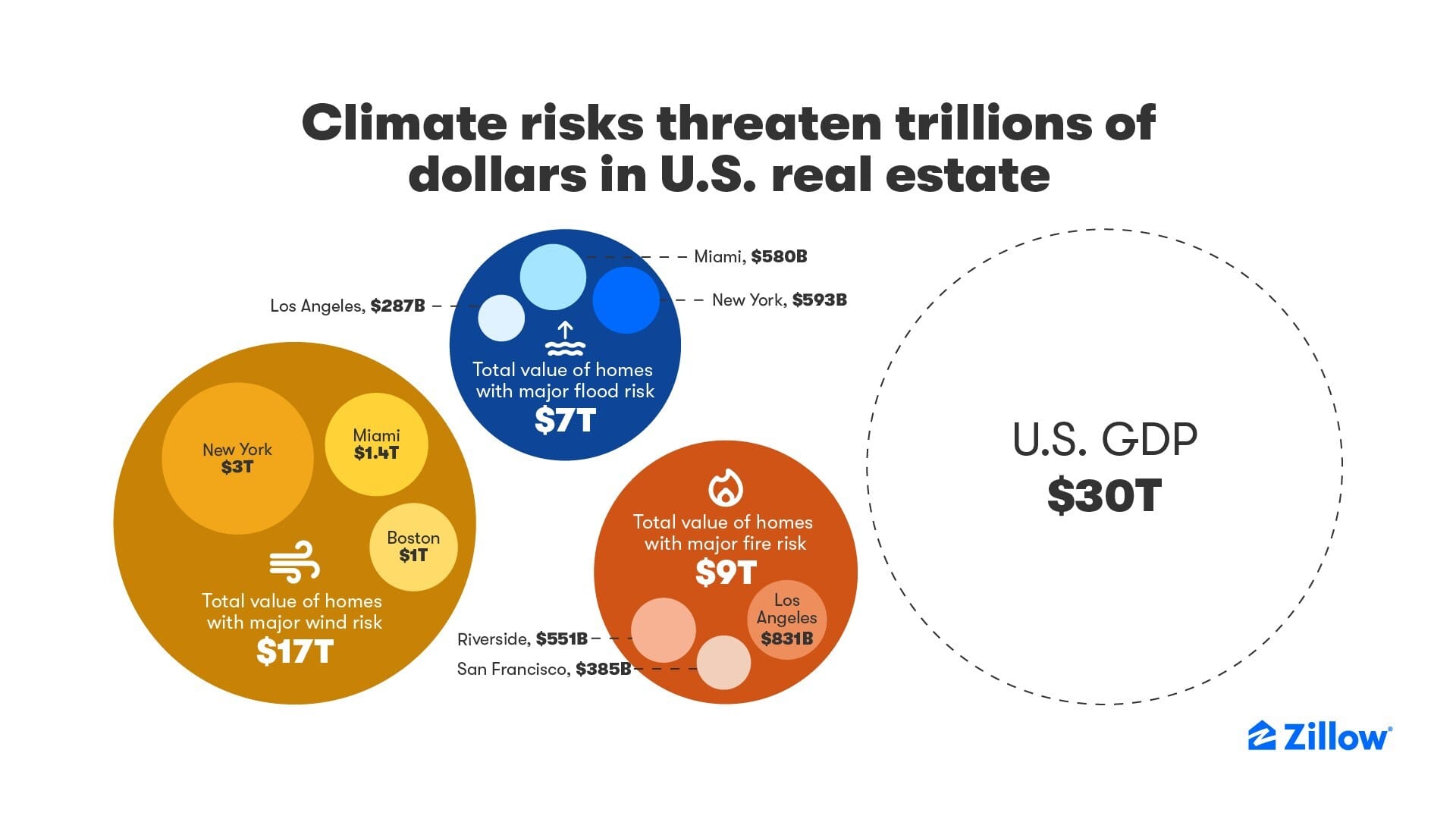

Zoom out further: a Cotality analysis found more than 2.6 million homes across 14 Western states, with roughly $1.3 trillion in reconstruction value, sit in moderate or higher wildfire risk zones. Over a million of those are classified as "very high risk."

This isn't a California problem. FAIR Plans across the country now cover nearly 3 million properties with exposure exceeding $1 trillion, according to the Insurance Information Institute. Former California Insurance Commissioner Dave Jones has called for a federal reinsurance program to backstop state FAIR Plans—because the current model is breaking.

Everyone from utilities to banks to insurers is drowning in climate risk scores. Almost nobody has a reliable way to turn those scores into decisions, workflows, and compliance artifacts that satisfy regulators and boards.

That's the opportunity.

Don't build another climate model. Build the execution layer that sits on top of all of them.

The Invisible Tax on Every Ratepayer

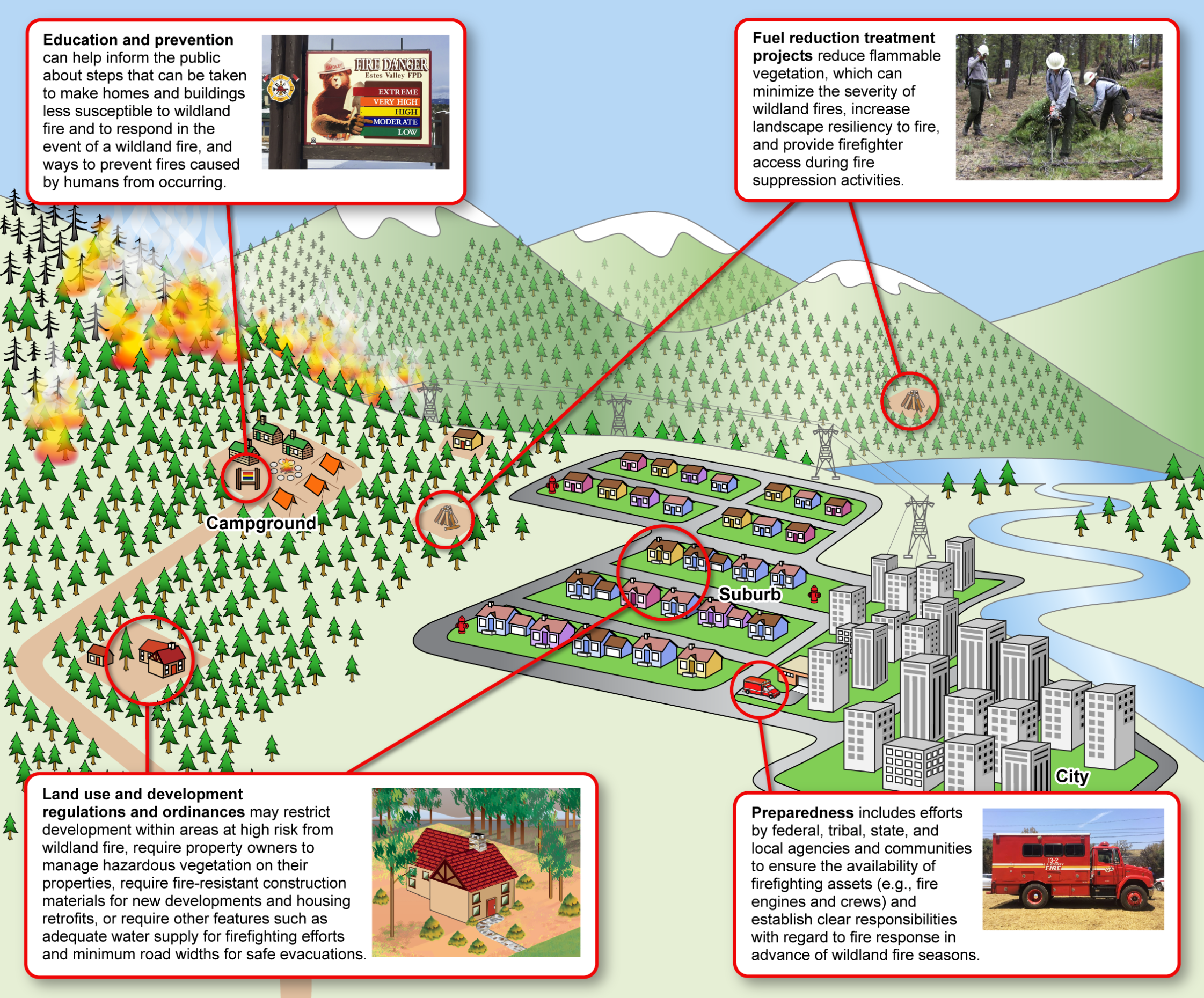

When PG&E's power lines sparked the Camp Fire in 2018, the company faced $30 billion in liabilities. It filed for bankruptcy in 2019 and eventually paid $25.5 billion to settle. Since then, California's three largest utilities have committed to spending $26.2 billion on wildfire mitigation between 2023 and 2025—up from $20.7 billion the prior three-year period.

That's $26 billion. From three companies. Over three years. Just for California.

Where does that money go? Vegetation management. Line hardening. Undergrounding. Public Safety Power Shutoffs. Covered conductors. Drone inspections. The CPUC noted these expenses "are projected to continue their upward trend due to climate-change-induced risks."

Research from UC Berkeley found that ignitions caused by vegetation striking power lines would have been 4.5 times greater in 2022 and 2023 without PG&E's risk reduction investments. The spending works. It's also enormous.

The big investor-owned utilities can handle this. PG&E has entire departments for wildfire mitigation. Southern California Edison claims it has reduced the probability of its equipment causing wildfires by up to 80% since 2018.

The problem is everyone else.

The Overlooked Goldmine: 2,800+ Utilities, Thousands of Small Lenders, and Insurers on the Edge

The U.S. has nearly 3,000 electric utilities. About 830-900 are rural electric cooperatives. Another 2,000 are public power utilities—municipals, public utility districts, irrigation districts.

These are the utilities serving small towns in fire country. They have boards of seven volunteers. They don't have wildfire mitigation teams. They have one guy who knows QGIS and another who updates the Excel spreadsheet.

And now they're being told to file wildfire mitigation plans.

The mandate wave is real:

- Montana passed House Bill 490 in 2025, requiring all electric cooperatives to develop wildfire mitigation plans by December 31, 2025, with public comment periods and board approval. The law ties liability protections partly to adherence to an approved mitigation plan.

- Utah passed similar legislation in 2020, requiring utilities and cooperatives to prepare wildland fire protection plans.

- California's Office of Energy Infrastructure Safety publishes annual requirements for publicly owned utilities and cooperatives.

- New Mexico has legislation underway to require electric cooperatives to develop wildfire mitigation plans.

- Oregon initiated rulemaking in 2020 for risk-based wildfire protection plans.

- Missouri's Public Service Commission sent letters to every utility in the state in May 2025, asking them to detail their wildfire mitigation strategies.

The responses revealed a patchwork. Ameren said its plan was "in its early development stage." Evergy expects to have a draft complete by the end of 2025. The Association of Missouri Electric Cooperatives acknowledged that having a well-structured plan "helps reduce liability exposure"—but many cooperatives are still figuring out what that means.

Layer on top the property finance side:

- Climate risk is already hitting balance sheets. First Street estimates lenders will lose $1.2 billion this year—and up to $5.4 billion in ten years—from climate-driven mortgage defaults.

- In an analysis of 29 historical flood events, First Street found that damaged properties outside FEMA flood zones experienced foreclosure increases 52% higher than properties inside the zones. Outside the zone means no mandatory flood insurance. No protection means default.

- Insurance markets in wildfire-prone states are cracking. California alone has seen FAIR Plan policy counts surge, and the program still needed a billion-dollar lifeline after the January fires.

Big, investor-owned utilities can hire Overstory, consultants, and entire "resilience" teams.

Small co-ops, public power districts, and regional lenders? They're staring at PDFs, GIS layers, and angry regulators with maybe one person who understands the data.

The Workflow Gap Nobody's Filling

Right now, the climate risk market is obsessed with modeling. First Street raised $46 million in 2024 to build "correlated risk models" and simulations. Overstory just raised $43 million for satellite-based vegetation intelligence. Moody's, S&P, Jupiter Intelligence, CoreLogic—they're all selling variations of the same thing: scores, maps, probabilities.

Here's the thing: when you ask two different climate models about the same property, they often disagree.

A Bloomberg analysis of flood risk models found they "clash with each other more than they agree"—matching on a simple risk metric only about one-fifth of the time. UC Irvine researchers compared their flood model to First Street's and found contrasting patterns—First Street's pointing to higher exposure for white and affluent communities, Irvine's for Black and disadvantaged populations. Same hazard. Completely different conclusions about who's at risk.

Nobody trusts a single score. But everyone needs to prove they did something with the data.

This is the gap.

Utilities don't need another risk model. They need software that takes the model they already bought, combines it with their asset data, and outputs a wildfire mitigation plan their regulator will approve, a budget their board will fund, and work orders their line crews can execute.

Banks and credit unions don't need another flood score. They need an underwriting workflow that flags properties, documents the decision, and creates an audit trail for when the OCC comes asking.

Insurers don't need another heat map. They need a retention tool that tells homeowners exactly which defensible space improvements will let them keep their policy—and routes that work to a vetted contractor.

The sexy problem (modeling) is largely solved. The ugly problem (doing) isn't.

The Product: What This Actually Looks Like

Think of this as the compliance and execution layer for climate risk—opinionated software tuned for regulated infrastructure.

Wedge #1: Wildfire Mitigation Co-Pilot for Small Utilities

Unlock the Vault.

Join founders who spot opportunities ahead of the crowd. Actionable insights. Zero fluff.

“Intelligent, bold, minus the pretense.”

“Like discovering the cheat codes of the startup world.”

“SH is off-Broadway for founders — weird, sharp, and ahead of the curve.”