Ever feel your heart rate spike when a stranger stands just a little too close in an empty elevator? That's not social anxiety. That's biology doing exactly what it's designed to do.

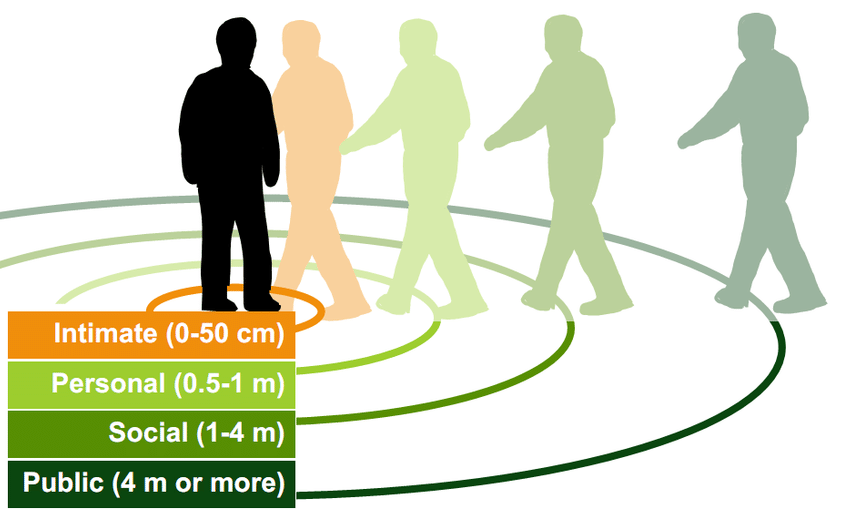

In the 1960s, anthropologist Edward T. Hall coined the term Proxemics—the study of personal space as a form of nonverbal communication. He discovered that every human walks around inside four invisible, concentric bubbles:

- The Intimate Zone (<1.5 ft): For lovers—or wrestling opponents.

- The Personal Zone (1.5–4 ft): Reserved strictly for friends and family.

- The Social Zone (4–12 ft): Where we transact business.

- The Public Zone (>12 ft): Where we ignore strangers.

Distance dictates relationship. When a business contact steps from 5 feet to 3 feet, they aren't just moving closer—they're unconsciously rewriting the terms of your interaction.

If a stranger breaches that 4-foot wall, your amygdala doesn't register "annoyance." It registers threat. Cortisol spikes before a single word is spoken.

We spend billions designing user interfaces on screens while ignoring the biological interface of physical space. Try conducting a cold transaction in a space reserved for intimacy, and the friction isn't accidental.

And we are currently watching the greatest violation of "Proxemics" in real estate history.

In 2026, becoming a landlord increasingly means building a unit 20 feet behind your kitchen—not buying a building across town. You're forcing a tenant, a fiscal stranger, directly into your Personal Zone. You share a driveway. You hear their TV. They see when you get home.

Traditional property managers don't solve this. They're built for scattered portfolios across zip codes, not managing the neighbor across your fence. They optimize for assets, not the psychological reality of living 20 feet from your customer.

The result: a massive Proximity Gap between what homeowners need and what the market provides.

ADU economics already pencil out. In California, even a modest 500-square-foot backyard unit rents for $1,800–$2,500/month. Construction costs run $150,000–$250,000, financed at 7–8%. At 75% occupancy, net operating margins hit 25–30% after expenses.

But margins mean nothing if you can't stomach the proximity. Most homeowners bail after 18 months—not because the math failed, but because nobody taught them how to be a landlord to someone they can see from their living room window.

The play: build the operating system that manages this new proximity. Not property management software. Proximity management infrastructure.

Control 100 of these backyard units at $220/month management fees, and you're looking at $22,000 in monthly recurring revenue. Do it right, and homeowners won't just tolerate the setup—they'll add a second ADU.

The market keeps talking about the housing crisis. Nobody's talking about the proximity crisis that's stopping homeowners from solving it.

Read the full playbook here:

One in five new California homes is now an ADU. The post-construction infrastructure to run them profitably doesn't exist yet.

From the Vault:

DoorDash's Zesty proves taste graphs beat social graphs. Beli and Letterboxd validated the model. The infrastructure layer is wide open.

Creator-driven foot traffic is already a $15B market. What's missing: performance attribution infrastructure that small businesses trust and pay for.